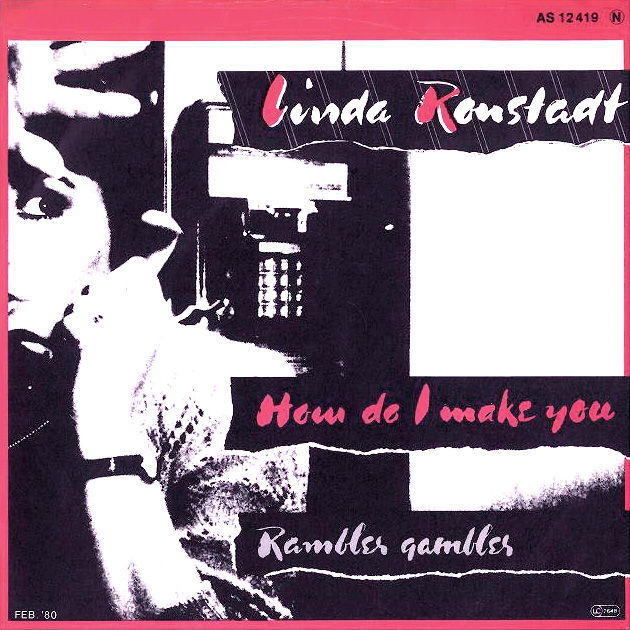

Linda Ronstadt – “How Do I Make You”

- Richard Challen

- Jun 26, 2020

- 10 min read

TOP 40 DEBUT: February 9, 1980

PEAK POSITION: #10 (March 22, 1980)

For half a decade, Linda Ronstadt ruled the world. The Arizona-born vocalist had spent the early part of the Seventies honing her craft in the trenches of the male-dominated club circuit, wowing audiences with her powerful pipes even as her records for Capitol failed to sell. (Her one Top 40 single during this period, the heartrending “Long Long Time,” peaked at #25. It’s a 9.) Only when she was halfway out the door to Asylum Records did Ronstadt land her breakthrough: Heart Like A Wheel, the first in her record-setting series of seven consecutive platinum albums. The leadoff single, a sassy, swaggering rendition of Clint Ballard’s “You’re No Good,” hit #1 on February 15, 1975, becoming her first and only chart-topper. (It’s a 10.)

On December 3, 1977, Simple Dreams knocked Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours off the top of the Billboard 200 on its way to selling over three million copies; a week later, she became the first act since the Beatles to place two songs in the Top Five simultaneously. By the end of the decade, Ronstadt was arguably the most famous female musician in America: a top-grossing concert draw and multi-platinum hitmaker, a pop pinup on roller skates with the governor of California on her arm, a golden-voiced chanteuse dubbed “Rock’s Venus” by no less an authority than Rolling Stone. (Of course, they also put her on the cover wearing nothing but a red lingerie slip, because Rolling Stone, like most of the Seventies music press, were deeply, deeply sexist.)

In some respects, Linda Ronstadt’s first album of the Eighties continued her five-year winning streak. Mad Love set a record with its Top Five debut—the first such placement for a female solo artist in Billboard history—and quickly garnered its creator another Rolling Stone cover (her sixth) and another platinum certification (her seventh). But Mad Love turned out to be the stylistic curveball no one saw coming. It was a record driven by contemporary sounds, abandoning Ronstadt’s well-established formula of country-flavored oldies in favor of New Wave pastiches and Elvis Costello covers, and it was anticipated by a single as short, sharp, and shocked as anything she had ever recorded—or would ever attempt again. Critics were divided; audience reaction was equally mixed. Even now, “How Do I Make You” tends to split the Linda Ronstadt fanbase like no song before or since. Funny how people reacted once the “Queen of Rock” decided to start rocking for real.

Linda Maria Ronstadt could basically sing anything. She got her start performing with the Stone Poneys, a folk-rock trio best known for their #13 hit “Different Drum,” but those early albums turned out to be merely the tip of her stylistic iceberg. As the years progressed, Ronstadt’s voice evolved into a thrillingly emotive, remarkably versatile instrument, equally adept at handling jazz standards, traditional mariachi music, or spunky studio pop. Her sweet spot, at least for most of the Seventies, lay in the middle ground between country and soft-rock, where she forged a distinctly Southern Californian blend of the two, mixing the easy sexuality of Carly Simon with the manicured layers of her former backing band, the Eagles.

Ronstadt was never really a songwriter; her core strength came from interpretation. She often did her best work when tackling lesser-known material from rock’s more idiosyncratic figures: J.D. Souther, Neil Young, and especially Warren Zevon. (The late, great, still-underappreciated Zevon freely admitted that publishing royalties from Linda’s multiple covers brought in way more revenue than his own recordings.) At first glance, the young, bespectacled Elvis Costello brandishing his guitar like a weapon on the cover of 1977’s My Aim Is True seemed miles removed from Ronstadt’s particular brand of countrified pop. But he still wrote in a voice instantly identifiable—and distinctly male. For anyone paying careful attention to her previous cover choices, Ronstadt’s sweetly sighing take on “Alison” (from 1978’s Living In The USA) made all the sense in the world. She would lean even further into Costello’s jagged writing—and equally jagged sonics—with her next album.

The main criticisms lobbed towards Ronstadt and her longtime producer/collaborator Peter Asher usually involved risk—or rather, the lack thereof. Too often, her most intriguing song selections got relegated to album deep cuts; the singles played it frustratingly safe. “Heat Wave,” “That’ll Be The Day,” “Tracks Of My Tears”: These were all big hits, but obvious ones. Just because Ronstadt could sing the phone book didn’t mean we needed her versions of already-definitive originals from Smokey, and Buddy, and Roy. Still, Asylum Records seemed reluctant to change a winning formula. Living In The USA went double-platinum off the strength of two big, obvious singles (originally performed by Chuck Berry and Smokey, again), “Alison” shared album space with the bajillionth cover of “Love Me Tender,” and Ronstadt inched ever closer to the dreaded no-man’s land of comfort food and Anne Murray.

Mad Love, then, came along in the nick of time, even if its “confrontational” reputation doesn’t quite hold up under close scrutiny. It was advertised as Ronstadt’s “New Wave album.” (It’s not.) It was billed as her foray into “hard rock.” (It was not.) Mad Love did acknowledge the current zeitgeist more than any other Linda record had in years, thanks to three Elvis Costello numbers and three more borrowed from an obscure power-pop act called the Cretones. (Their debut effort, Thin Red Line, appeared within weeks of Ronstadt’s own release and promptly tanked; it absolutely deserves a reappraisal.) But Mad Love also pulled its own share of punches. Ronstadt still used most of the same L.A. session musicians from her previous albums; Asher made sure to include compositions first popularized a quarter-century earlier by the Hollies and Little Anthony. Guess which songs Asylum picked as the singles.

Predictably, the thought of a “pop princess” invading the cool kids’ turf brought out the ire of male rock critics. Rolling Stone slammed Mad Love in an infamous April 1980 review, criticizing its “calculated… salon approach” while accusing Ronstadt of “imitating” Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry. Costello himself went even further, calling her versions of his songs “sheer torture. Dreadful. It’s a total waste of vinyl.” Confused fans purchased the LP, then sent it straight to the dollar bins. (In an era famous for album longevity, Mad Love never reached #1 despite that splashy #5 debut in mid-March, and it would fall out of the Top 10 before summer.) Even in 2019’s comprehensive documentary Linda Ronstadt: The Sound Of My Voice, the record is pictured but never mentioned. Ronstadt’s own autobiography, Simple Dreams: A Musical Memoir, dismisses Mad Love with a single line: “My first digital album.”

Four decades later, Ronstadt’s strange little experiment now boasts its own small-but-passionate cult, a cadre of fans who appreciate her inside-out reworking of “Party Girl” or simply enjoy hearing those honeyed vocals recontextualized in a post-punk setting. Over the years, Mad Love’s critical rep has improved as well. Costello started coming around as early as ’89: “I was so snotty about Linda Ronstadt’s covers. I was just being punky and horrible.” By 2019, he was openly weeping during a Sound Of My Voice screening and praising Linda’s work on his website. Rolling Stone reversed course too, just in time for the album’s forty-year anniversary: Ronstadt’s “fascinating failure” from 1980 was now, in 2020, “one of her career highlights.”

Personally, I admire the determination behind Mad Love, if not always the end result. Ronstadt (mostly) blew up her own formula at a time when it was still paying commercial dividends, and she did so without any advance warning, shifting from golden oldies to cutting-edge rock in roughly fifteen months. (I’m picturing Taylor Swift going directly from “You Belong With Me” to “Bad Blood” with nothing in between.) At the same time, Ronstadt still preserved her own artistic ethos; she wasn’t jumping headfirst into New Wave but simply “looking for songs to record.” Sometimes the fit was poor. Sometimes the slickness of the session musicians—drummer Russ Kunkel, bassist Bob Glaub, guitarist Dan Dugmore—proved antithetical to the sloppy spirit of the original compositions. But sometimes, Ronstadt and her cohorts caught lighting in a bottle.

“How Do I Make You” is a two-minute blast of pure energy, a stripped-and-sparse Fifties-style rave-up with a safety pin through its nose. It’s the sound of SoCal’s prom queen letting her hair down—or, more accurately, chopping it all off. Ronstadt doesn’t possess Debbie Harry’s inherent toughness or effortless cool, and she never comes close to losing control, but give her credit: She looks this song in the eye and absolutely goes for it. The edge on her voice during that final “dream about me” series isn’t strain but precision, a top-notch singer added as much grit as necessary and nailing it perfectly. Or to make the comparison more blunt: “Debbie Harry has nothing on Linda Ronstadt.” (That’s her longtime guitarist, Danny Kortchmar, quoted in a recent Billboard article, and it gets better: “Harry is a pop star and that's great; she's good at that. Ronstadt is one of the greatest singers who ever fucking lived, man. She will kill you in a minute.”)

Give Ronstadt’s bandmates credit as well, if only for the way they transposed a fair amount of punk spirit into the expensive environs of L.A.’s Record One studio. Kunkel kicks off the proceedings with a full five-second drum roll, building in intensity like a stampede coming around the corner. (Loverboy would later swipe this intro for their own ’83 hit “Hot Girls In Love,” which is just bizarre.) Backing vocalist Nicolette Larson matches Ronstadt beat for beat, the Flo Ballard to her Diana Ross. (Larson will appear on this site very soon.) The mix has that great, super dry bite from Joe Jackson’s Look Sharp. The guitars are pure treble and bright enough to take your head off, while the slightly sloppy solo comes courtesy of Mark Goldenberg, lead singer and chief songwriter for the aforementioned Cretones. “How Do I Make You” wasn’t one of Goldenberg’s own compositions, though. Instead, it arrived via a soon-to-be-huge songwriter just trying to rip off a Knack song.

Billy Steinberg grew up in Palm Springs, California, where he worked for his father’s table grape business while trying to break into the music industry. In 1979, he formed Billy Thermal, a power-pop quartet eventually signed to Planet Records, a label owned by superstar producer Richard Perry. (Their lone album got shelved in 1980, but finally saw a belated release in 2014.) Thermal’s guitarist, Craig Hull, was dating Wendy Waldman, a backing vocalist in Ronstadt’s live band. One night, without Steinberg’s knowledge, the couple played some unreleased Billy Thermal demos for Ronstadt. She gravitated towards one song in particular: a bouncy New-Wave number with a rhythm heavily influenced by “My Sharona.”

“I thought it was just like ear candy.” That’s how Steinberg later described his initial reaction to the Knack’s monster #1 hit, which does, in fact, sound a lot like Billy Thermal’s original version of “How Do I Make You.” Wisely, Ronstadt sped up the tempo, lost the demo’s herky-jerky rhythm, and created a far-less-derivative final product. (She probably also saved Steinberg from an inevitable copyright suit in the mid-2010’s.) “How Do I Make You” wound up being the first Top 10 writing credit of Steinberg’s career. It wouldn’t be his last. In 1981, he joined forces with fellow songwriter Tom Kelly; by Christmas of ‘84, they would land their first of five eventual #1’s. (The Steinberg/Kelly duo will be all over this site in a few virtual years.)

“How Do I Make You” might’ve been a springboard for Billy Steinberg, but it turned into a dead end for Ronstadt. The single reached the Top 10 in a mere eight weeks, only to immediately stall out as the Mad Love backlash began to set in. Asylum Records hedged their bets from the outset, throwing the tonally opposite “Rambler Gambler” onto the B-side before servicing the track—a traditional folk number actually recorded during the Simple Dreams sessions—to country radio. (“Rambler Gambler” peaked at #42. It has still never appeared on any official Ronstadt album or compilation.)

Perhaps Asylum were motivated by the tandem success of “An American Dream,” the Dirt Band’s concurrent country-pop hit with Ronstadt featured on prominent guest vocals. (Knowing that Rocker Linda squared off with Country Linda over three weeks in February 1980 is the kind of random trivia that makes chart watchers irrationally excited.) Or maybe the label just wanted a return to a proven commodity. Mad Love’s second single, a cover of a ballad dating back to 1965, got rushed to radio even as the first single was still ascending. It would debut, at #46, in the same week “How Do I Make You” fell out of the Top 10, as if everyone—programmers, listeners, even Asylum itself—couldn’t wait to get the old Ronstadt back.

I don’t want to speculate on Linda’s thought process going into the Eighties; for all I know, Mad Love might’ve always been planned as a detour, rather than a destination. But it sure feels like Ronstadt made a valiant, gutsy attempt to truly shake up her sound for the new decade, only to immediately receive blowback from all corners. In that situation, who can blame her for reversing course as soon as possible? Before the year was over, she would be singing Gilbert & Sullivan on Broadway. By 1983, she’d be doing standards backed by a Nelson Riddle-conducted orchestra.

These were risky ventures, of course, even more risky than releasing a thirty-minute album of power-pop. But unlike Mad Love, they were also met with critical plaudits and near-universal praise. Ronstadt responded accordingly; she would keep taking artistic chances, but “rock” would never again factor into the equation. Again, I don’t blame her one iota. It’s just frustrating to imagine the kind of forward-thinking music she might’ve made over the remainder of the decade, had certain gatekeepers viewed her more like an ally than a carpetbagger.

Here’s one final piece of chart arcana to slam this point home: On February 9, 1980, two singles by female artists both entered the Billboard Top 40. Five spots below the #35 debut of “How Do I Make You” came a 27-year-old singer named Pat Benatar, making her first Top 40 appearance ever. Like Ronstadt, Benatar was a powerful vocalist capable of handling numerous genres. Like Ronstadt, Benatar was the rare woman performing in a male-dominated idiom, fronting a band composed mainly of the opposite gender. Like Ronstadt in 1980, Benatar cut her hair short and decided to rock. But unlike Ronstadt, Benatar had no baggage, no expectations, and no restrictions. The tale of Pat Benatar in the Eighties is that of a woman finding her own highly successful lane of driven, female-centric rock n’ roll. The tale of Linda Ronstadt is that of a superstar retreating, prematurely, from that same lane, leaving only one brave, bracing single behind.

GRADE: 8/10

I WANT MY MTV: The official promo for “How Do I Make You” features a totally different sound recording, cut live on set for the cameras and arguably more rambunctious than the studio original. If anything, the song makes better sense this way: looser, faster, closer to a true organic rock sound and topped with a killer Linda vocal. But you can also see one reason why the image-obsessed music press hated Mad Love so much; there’s a chasm of cool between Goldenberg’s ready-for-MTV wardrobe and Kunkel’s unfortunate Larry David ‘do.

BONUS BITS: The Chipmunks’ version, taken from their album Chipmunk Punk and spotlighting a rare lead performance from Simon (the one with the glasses), remains the only major cover of “How Do I Make You” ever released. Proof, obviously, that no further interpretations are necessary once the Chipmunks deliver the definitive one.

The best track of her career, in my opinion. And I have been a devoted Ronstadt fan for almost 50 years!

This has to be the first time I heard this song since 1980 literally! I do remember this song being out and playing on the radio if however momentarily which is explained by you, Richard, pointing out how it basically rose quickly up and then quickly fell off the charts. I think I have to credit that very 'Chipmunk Punk' record ad for remembering "How Do I Make You" to this day. Otherwise, I may have forgotten all about the song. Seeing that commercial the numerous times I did at the time had to have added assurance of this. I'm pretty sure I saw the ad more than I heard the actual Ronstadt version on the radio. Without looking it…

Totally agreed on another quality write-up today, Richard. I love a bit of Ronstadt and she had the most incredible set of pipes and the way that she detoured in the 80s, often bravely against record company advice, plus ended up ruling in nearly all of these territories is the stuff of legends and speaks much to her own determination and independence as an artist. I remember hearing her interviewed for a UK radio show in the early 80s and picking some of her favourite music and I was amazed at how thoughtful, articulate and determined she came across - and she really stood out from the crowd for her intellect and intentionality. I could totally see how she came…

Thanks guys! I absolutely LOVE Zevon, who I won't get to write about in this column obviously, so I threw him a little love here. I appreciate Linda for introducing the masses to his songwriting (much like Judy Collins for Leonard Cohen).... I do think Warren does better versions of his own songs. He brings an edge that Ronstadt doesn't really possess. (Linda's best Zevon cover might be "Mohammed's Radio," though. That one has some bite.) Just a heads up that I'm actually gonna be gone for a few days next week. (First time since March!) So no column on Monday.... We'll resume normal operations in a week though. Be safe and thank you all for reading!

I never thought to equate her Mad Love era with Pat Benatar, who had much more attitude. And I didn’t know this song was a cover, but I should have realized it given the rest of her career. I liked both the song and a followup from the album, “I Can’t Let Go.”