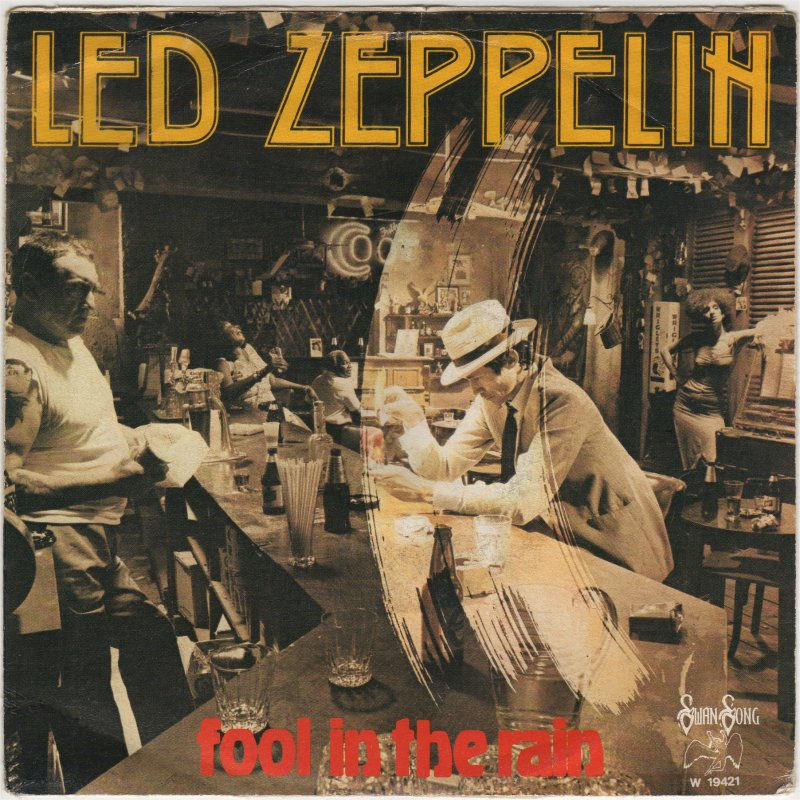

Led Zeppelin – “Fool In The Rain”

- Richard Challen

- Apr 24, 2020

- 9 min read

TOP 40 DEBUT: January 12, 1980

PEAK POSITION: #21 (February 16, 1980)

Led Zeppelin would’ve had a fascinating Eighties. They might’ve embraced their elder statesman role. They could’ve gone off the deep end experimentally. I could see Robert Plant pushing them to embrace angular modern rock and, ideally, form a more-perfect version of his own (eventual?) solo career. Or perhaps the creeping conservatism of guitarist Jimmy Page would’ve led to a series of safe, disappointing albums. (Probably not as disappointing as The Firm, but still.)

There’s no guarantee Zeppelin would’ve even survived the Eighties. It’s entirely possible they crash and burn; just as likely they run out of gas, like The Who, or become a slick corporate parody of themselves, like the Stones. But good or bad, I can’t imagine their trajectory being boring. And as the finer moments of 1979’s In Through The Out Door suggest, there was every chance Zeppelin could’ve cooked up another masterpiece and surprised us all.

Of course, we never got the opportunity to find out. Shortly after midnight on September 25, 1980, drummer John Bonham passed out following a long day of drinking—and didn’t wake up. His unresponsive body was discovered the next afternoon by bassist John Paul Jones and tour manager Benji LeFevre. A coroner’s inquest determined that he’d consumed forty shots of vodka over a 24-hour period, before eventually choking to death on his own vomit. Bonham was just 32 years old.

A planned North American tour, scheduled to begin on October 17th (the band’s first since 1977), was cancelled. Two months later, via a December 4th press release, Led Zeppelin officially disbanded. Outside of a few one-off reunion shows, the surviving members never reformed; later albums of “new” material came from archival tapes. The recorded legacy of Zeppelin, then, ends with their final studio release, In Through The Out Door, and the last single released during the band’s lifetime. In the moment, “Fool In The Rain” seemed to anticipate an entirely new chapter for one of the most relentlessly creative bands of the decade. Instead, it became an unintentional farewell, a frustrating glimpse into a future that never happened.

In Through The Out Door arrived over three years after Presence, the longest gap between albums in Led Zeppelin’s lifetime. Up until that point, the band had been releasing records at a dizzying once-every-twelve-months pace, and evolving just as quickly. Less than three years elapsed from the blues-on-steroids caterwauling of “You Shook Me” (1969’s Led Zeppelin I) to frickin’ “Stairway To Heaven” (1971’s Untitled, AKA Led Zeppelin IV); barely three more to reach the dizzying heights of “Kashmir,” “Ten Years Gone,” and the rest of 1975’s double album/career pinnacle Physical Graffiti. Thirteen months later, exhaustion finally caught up with them. Excluding the posthumous odds-and-sods collection Coda, Zeppelin never released a bad studio album, but if they had, it would’ve sounded a lot like Presence: two of the greatest tracks the quartet ever recorded (“Achilles Last Stand” and “Nobody’s Fault But Mine”), plus five others remembered only by diehards.

Plant had been seriously injured in a car accident in August 1975, scuttling the band’s tour plans and prompting the rushed recording and release of Presence instead. A run of North American concerts finally commenced on April 1, 1977, only to be cut short on July 26th, when news arrived that Plant’s five year-old son had died of a stomach virus. The distraught frontman caught the next plane back to England; Zeppelin never played live in America again. It would be a full year before all four members officially reconvened, this time to begin work on what would become their final studio album.

Zeppelin released In Through The Out Door in August ’79 into a radically different musical landscape; its reception was, to put it kindly, ”mixed.” Even now, this remains the most polarizing record in the Zeppelin canon: loved for its freewheeling experimentation (the ten-minute “Carouselambra” might be the weirdest thing the band ever recorded, which is truly saying something); hated for its overreliance on synthesizers, compounded with an under-reliance on the guitar work of Jimmy Page. Some regarded the additional keyboards as pure calculation, a blatant attempt from aging dinosaurs to stave off extinction in the age of new-wave and punk. In reality, they were masking an uglier truth. Page, deep in the throes of heroin addiction, wasn’t writing songs, leaving John Paul Jones to pick up the slack.

Jones was always Zeppelin’s secret weapon, a criminally underrated jack-of-all-trades proficient on bass, keyboards, and a variety of stringed instruments. His skills with arranging arguably influenced the group’s sound as much as Page’s studio wizardry, and they certainly came to the fore once the latter’s drug use began affecting his creative output. Most of In Through The Out Door began with Jones and Plant, working together for the first time in the band’s career. The “relative clean” half of the band took to laying down the album’s basic framework during daylight hours; Bonham and Page, the alcoholic and the addict, showed up late, adding their parts in the middle of the night. Sometimes, they didn’t show at all.

Given the circumstances, it’s hard to fault Out Door for bearing little resemblance to anything else in the quartet’s back catalog. The saving grace is how well the record works on its own terms. Strip away all the classic rock baggage surrounding the idea of “Led Zeppelin,” and you’ll finally start to appreciate In Through The Out Door as the odd, artsy album it always was—from the creeping dread of “In The Evening,” to the synth-heavy sigh of “All My Love” (Plant’s tender tribute to his late son), to whatever the hell’s happening on “Carouselambra.” And yes, you might even wind up acknowledging “Fool In The Rain” for being the band’s most gutsy—and successful—stylistic swing ever.

Zeppelin always had a spotty track record when it came to aping other genres. “D’yer Mak’er,” a Top 20 single in December ’73, is a hoot-and-a-half (and a 9), but its bastardization of reggae probably insulted the country of Jamaica even more than the terrible pun in its title. The great, stomping “Trampled Under Foot” feels like ”funk” filtered through metal shavings; “The Crunge” is a James Brown homage so off-the-mark, it took me years to realize it was supposed to be a James Brown homage. But “Fool In The Rain,” bless its heart, works as an honest-to-goodness Latin song: Zeppelin-ized, of course, but otherwise as close to Havana as a bunch of skinny white boys could get in ’79.

The first thing you notice is the groove. Jones (on piano and bass) and Page (on relatively subdued guitar) lock into a Cuban-styled swing pattern comprised mainly of triplets, while Bonham plays a half-time shuffle underneath. It’s an exercise in polyrhythms; for the musical layman, imagine the piano getting six beats in a measure while the drums play four. This is the kind of thing that, frankly, hurts your brain to count. It’s also the thing Zeppelin excelled at: taking super-complicated time signatures and making them swing.

For the first minute or so, “Fool In The Rain” plays it straight. The endlessly looping riff keeps looping, endlessly. Plant adds a simple vocal melody on top. The gaps in the pattern become the pattern. Then out of nowhere, Page drops a Spanish-styled 12-string figure, Bonham uses his ride cymbal to make the six beats explicit, and the entire track tilts deliriously on its axis. It’s a heady, disorienting twist—and then, moments later, it’s gone. Few rock bands in ’79 were capable of pulling this off. Zeppelin does it, repeatedly, throughout the entire song, just for kicks.

Speaking of out of nowhere: Just as you’re getting a handle on this quirky little song, along comes the whistle. And the double-time piano. And suddenly we’re dropped headlong into the middle of a Brazilian carnival, an explosion of percussion and tamborims and Plant shouting “I gotta get it all!” even as he’s swallowed up by the mix. (Where’s Page in all this? Does he even play a note? What other Zeppelin song hits its climax with Jimmy Page absent from the proceedings?!?)

The entire section—a whirling, surprisingly authentic approximation of the “batucada” subset of samba—happened thanks to the ’78 World Cup. Argentina was hosting the tournament; watching on TV, Jones and Plant kept noticing the distinctive rhythm of the chants echoing through the stadium. So they decided to throw a “samba breakdown” into the middle of the other Latin-tinged tune they were writing—again, just for kicks. And somehow, they made it work. If you want to know why Zeppelin still matters, fifty years on, “the samba breakdown in the middle of ‘Fool In The Rain’” might be as good an explanation as any.

That’s far from the only essential moment of “Fool,” of course. Coming out of the breakdown—with the whole band downshifting, save Bonham, who flies across his kit like a man possessed—might be more thrilling than going in. Plant’s final lyrical denouncement, in which the cause of all our narrator’s romantic woes turns out to be poor directional skills, puts a genuinely clever period on an otherwise standard tale. And as much as Page gets sidelined for the rest of the song, he eventually delivers a solo as idiosyncratic as it is iconic: squelchy and sloppy, boasting a ray-gun tone created from a multi-octave Blue Box fuzz pedal, and designed to flatten everything in its path.

Finally, the glue holding all these polyrhythms and piano lines together? That truly tremendous drum part. John “Bonzo” Bonham spent every one of his thirty-two years on Earth swallowing great big gulps of life, in both good and terrible ways, and that voracious appetite manifested itself every time he sat behind a drum kit. Rock n’ roll always had a love for “wild man” drummers: Keith Moon, Mick Fleetwood, Ginger Baker. For my money, none could singlehandedly elevate a song the way Bonham did.

He wasn’t particularly precise; he didn’t blow you away with technical prowess like Peart or Bruford. But on record, no one else sounded as raw, as powerful, as primordially heavy as Bonzo. His playing doesn’t just support. It practically leaps out of the grooves. Why did early hip-hop consistently tap into his energy? How does a simple cymbal crash take your head off? What kind of alchemy is occurring in a standard 4/4 beat to leave you spellbound for eight solid minutes? That’s the singularity of Bonham. When it came to pure, primal swagger, he was a class of one.

The beat Bonham plays on “Fool In The Rain” is a variation of the “Purdie Shuffle,” named after its creator, legendary session drummer Bernard Purdie. It’s a skittering, syncopated pattern, first popularized on the Steely Dan album track “Home At Last” and since copied by everyone from Toto to Death Cab For Cutie. It requires proper feel, perfectly placed grace notes, and true technical skill. In other words, it’s incredibly hard to play. And Bonzo doesn’t just pull it off. He absolutely crushes it.

During the recording sessions for In Through The Out Door, John Bonham was abusing both alcohol and heroin. (The former was, sadly, par for the course; the latter definitely wasn’t.) He was two years away from drinking himself to death. I have no idea how he delivered his “Fool In The Rain” performance under those conditions. But I’m insanely glad it exists. Somehow, Bonham managed to convey all the grace and finesse the “Purdie Shuffle” demands, without sacrificing an ounce of his piledriving force. Hearing his isolated drum track is like watching a rhino don ballet slippers and dance Swan Lake. You can’t quite believe it’s happening—even as it’s happening.

“Fool In The Rain” peaked at #21 on the Hot 100, making it one of the band’s biggest singles in America. Officially, the song ranks fifth: trailing “Whole Lotta Love,” “Immigrant Song,” “Black Dog,” and the aforementioned “D’yer Mak’er,” but ahead of other Zep classics like “Rock And Roll” and “Over The Hills And Far Away.” (Can we all agree to end the common misconception that “Led Zeppelin never released singles” once and for all? Please?) And yet, for large sections of the fanbase, “Fool In The Rain” remains as polarizing as its parent album. Some argue it’s one of the best songs the quartet ever made; others label it the worst kind of sellout.

Personally, I understand the criticisms while also soundly rejecting them. “Fool In The Rain” might not be an all-time track, but on the other hand, everything about the song—its sense of adventure, its willingness to travel far outside the expected hard-rock norms—reminds me why I fell in love with this band in the first place. That freewheeling spirit is what gave Zeppelin their magic; it’s also what made their unique alchemy impossible to replicate. The Eighties would soon be overrun with dozens of hair-metal acts trying their best, strip-mining Zeppelin’s surface layer for parts while engaging in various forms of slavish hero worship. But the real thing, in all its crazy, complicated glory? That was already long gone.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BITS: Here’s the legendary Mexican rock group Maná paying ultimate tribute to a band of British blues hounds by offering up a Spanish-language version of “Fool In The Rain” (“Tonto En La Lluvia”) that barely changes a note, yet still translates seamlessly. Recorded for the 1995 compilation Encomium: A Tribute To Led Zeppelin, Maná’s track somehow missed the cut before being added to later pressings. (In hindsight, they should’ve used this and dropped that awful 4 Non Blondes cover instead.)

A huge Zeppelin-fan I became halfway into high school. Knew of them prior. My parents had their albums growing up; would play with (spin) the Led Zeppelin III album cover. 2nd-half of high school my 'Holy Trinity' was they, Floyd, and Yes pretty simply (the earlier into the '70s, the better) with the Beatles being too obvious for me to feel ever having to mention all that much.

'In Through the Out Door', to me, is the weakest of their output. It is one of the first three CDs that I got, though, back in 11th grade; but only because I already had their other material on cassette albeit an actual cassette or a blank cassette recording off one of…

It defies logic and is not consistent with the list of bands I do like, but I was never a Led Zeppelin fan. Growing up, Led Zeppelin was the domain of the burnouts, and I wasn't one, so I rejected their music, and the most beloved Zeppelin songs were the once I liked the least.

With all that said, maybe it's not so surprising in context that I love "Fool In The Rain." I took to it the moment I first heard it, and I embraced it without prejudice. The thing is, I certainly don't hear it as a sellout. Maybe the Zeppelin loyalists didn't like it because it was more melodic and less gut-crunching, but it was hardly a…

Great writeup as usual, Rich. I wasn't a Zep fan UNTIL this album! Loved the creativity, the added texture. The drum track you provided is mesmerizing, thank you! A certain weekend spent at a girl's house coinciding with the parents absent for a day, and a stack of albums (Styx Equinox, Crystal Ball, and Zep's In Through The Out Door) made for a memorable afternoon, the day of the Super Bowl in Jan. 1980.

Fantastic writeup. Zeppelin is very hit-and-miss for me (they can be awful just as often as they could be great - to use an In Through the Out Door example, Plant duetting with himself on "Hot Dog" is a legendarily terrible idea), but I agree with everything you say on this song's brilliance.

My best friends in high school adored Zeppelin. Unfortunately, I never quite made the same connection with the band, though I sincerely tried. Fool in the Rain, while I’d never actively seek it out, is still an interesting song to me, and much credit to the band for successfully pulling off such a creative twist.